Victor and manonamora report the results from the fourth quadrennial poll of the community’s all-time favorite interactive fiction.

Every four years, starting in 2011, one of us (Victor) has organised a community poll on the best interactive fiction ever written; this year the other one of us (manonamora) joined in and did most of the data processing. The rules of the poll have remained consistent over the years: everyone can participate by making a list of at least one and at most twenty titles. Each title equals one vote. The votes are then tallied, and a list emerges that reflects to some extent what the community views as the best interactive fiction so far.

What is ‘the community’? How far is ‘to some extent’? And, for that matter, what is ‘interactive fiction’? To start with the last of these questions, the organisers have always been vague about this on purpose. One of the aims of the poll is to find out what this community, the ‘interactive fiction community,’ considers to be the works that are central to its identity. The organisers prejudging this issue would be counterproductive and might also stop people from participating.

Of course, this only makes the first question more pressing. What is this community whose opinion we are soliciting? This is all the more important because there are numerous communities that could be described as focused on interactive fiction in one form or another. The impact of the organisers’ decision to post the call for votes on the intfiction.org forum, rather than on, say, the Failbetter Games forum or the Choice of Games forum, cannot be underestimated: it completely changes which people will react and which games will end up being voted for.

The best way to characterise the participants in the poll may be this: they are people who might hang out at intfiction.org, who might engage with the Interactive Fiction Competition and the Spring Thing, and who might post or read reviews on the IFDB. This is certainly not a monolithic community. One person might be engaged in writing old school text adventures that run on legacy hardware, while another likes to explore deeply personal topics through choice-based narratives; and one person might hanker for weird experimental parser pieces, while another likes link-based exploration or resource management games. But even though it is not monolithic, it also does not encompass the full range of people who are engaged in interactive fiction.

Why not strive for this full range? In part because once you have people from relatively unconnected communities vote in the same poll, the poll turns into a sociological experiment to determine which community is larger, rather than an investigation into the artistic judgments of a particular group. If we did promote the poll on the Failbetter Games forum, then no doubt Fallen London would be the number one game; and while this would accurately reflect the size of its player base, it would perhaps not be very useful to get a sense of how this particular game relates to other games. This is not to say that a poll involving a much broader community than the one we have been actively trying to reach could not be interesting. But – and this is the second and more fundamental reason to not pursue this course for our particular poll – it would not have much continuity with earlier editions of the Interactive Fiction Top 50. It would not give us any insight into changing tastes and attitudes. If it were organised, it were better organised under another name.

(Of course one can legitimately ask why the first edition of the poll was not organised among a broader group of people. The answer is at least in part that the community around intfiction.org, which had evolved from that around the rec.arts.int-fiction and rec.games.int-fiction newsgroups, was much more isolated then than it is now. This was true both as a fact – some of the communities mentioned above just weren’t around at the time, or were much smaller than they are now – and as a matter of self-image, which was heavily centred on a shared history and the use of the parser.)

Having said all that, it should be stressed that the current poll was also promoted on social media, and votes could be sent in through email, so there were certainly participants who were not active forum members.

We still have to answer the second question: to what extent does the current poll reflect the views of the community? There were 880 votes cast by 59 people (an average of almost 15 votes per person). So that’s quite a large number of votes. However, these votes were distributed across no fewer than 341 games, for an average of about 2.6 votes per game. Since getting into the top 50 required 4 votes, the difference between games that did and games that did not pass the threshold should not be taken too seriously. Do the poll three months later, and a game could easily have three more or three fewer votes, totally changing its place or inclusion in the Top.

Luckily, creating am authoritative ranking from best to worst is not the purpose of the Top 50 anyway. Rather, we hope that the poll – the outcomes presented here, the full list of games linked to below, and the public comments made by many of the voters when they voted – serve as a powerful impulse to explore the wide world of IF games, both new and old, both those that are universally acclaimed and those to which only one or two people have wanted to draw our attention.

Results

There are 48 games which received 5 or more votes; once games with 4 votes are added, the total rises to 70. We make the same decision we made in the 2019 edition, and err on the side of inclusion, turning the Top 50 not into a Top 48, but into a Top 70.

| Place | Title | Author | Year | Votes |

| 1 | Counterfeit Monkey | Emily Short | 2012 | 26 |

| 2 | Anchorhead | Michael Gentry | 1998 | 21 |

| 3 | Spider and Web | Andrew Plotkin | 1998 | 17 |

| 4 | Hadean Lands | Andrew Plotkin | 2014 | 15 |

| 5 | The Impossible Bottle | Linus Åkesson | 2020 | 13 |

| 6 | The Gostak | Carl Muckenhoupt | 2001 | 12 |

| = | Photopia | Adam Cadre | 1998 | 12 |

| 8 | Eat Me | Chandler Groover | 2017 | 11 |

| = | Lost Pig | Admiral Jota | 2007 | 11 |

| 10 | 80 Days | inkle & Meg Jayanth | 2014 | 10 |

| = | Adventure | William Crowther & Donald Woods | 1976 | 10 |

| = | Blue Lacuna | Aaron Reed | 2008 | 10 |

| = | Curses | Graham Nelson | 1993 | 10 |

| = | The Wizard Sniffer | Buster Hudson | 2017 | 10 |

| 15 | A Mind Forever Voyaging | Steve Meretzky | 1985 | 9 |

| = | Superluminal Vagrant Twin | C.E.J. Pacian | 2016 | 9 |

| = | Suveh Nux | David Fisher | 2007 | 9 |

| 18 | Birdland | Brendan Patrick Hennessy | 2015 | 8 |

| = | Cragne Manor | Ryan Veeder, Jenni Polodna, et al | 2018 | 8 |

| = | Plundered Hearts | Amy Briggs | 1987 | 8 |

| 21 | According to Cain | Jim Nelson | 2022 | 7 |

| = | Coloratura | Lynnea Glasser | 2013 | 7 |

| = | Open Sorcery | Abigail Corfman | 2016 | 7 |

| = | Spellbreaker | Dave Lebling | 1985 | 7 |

| = | Suspended | Michael Berlyn | 1983 | 7 |

| = | The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy | Douglas Adams & Steve Meretzky | 1984 | 7 |

| = | Trinity | Brian Moriarty | 1986 | 7 |

| 28 | Aisle | Sam Barlow | 1999 | 6 |

| = | howling dogs | Porpentine | 2012 | 6 |

| = | The Archivist and the Revolution | Autumn Chen | 2022 | 6 |

| = | The Fire Tower | Jacqueline A. Lott | 2004 | 6 |

| = | The King of Shreds and Patches | Jimmy Maher | 2009 | 6 |

| = | The Wand | Arthur DiBianca | 2017 | 6 |

| = | Violet | Jeremy Freese | 2008 | 6 |

| = | Will Not Let Me Go | Stephen Granade | 2017 | 6 |

| = | Worlds Apart | Suzanne Britton | 1999 | 6 |

| = | Zork I | Marc Blank & Dave Lebling | 1980 | 6 |

| 38 | A Dark Room | Michael Townsend | 2013 | 5 |

| = | A Paradox Between Worlds | Autumn Chen | 2021 | 5 |

| = | Choice of Robots | Kevin Gold | 2014 | 5 |

| = | Computerfriend | Kit Riemer | 2022 | 5 |

| = | Grooverland | Brian Rushton | 2021 | 5 |

| = | Horse Master | Tom McHenry | 2013 | 5 |

| = | Make It Good | Jon Ingold | 2009 | 5 |

| = | Savoir-Faire | Emily Short | 2002 | 5 |

| = | Shade | Andrew Plotkin | 2000 | 5 |

| = | SPY INTRIGUE | furkle | 2015 | 5 |

| = | Wishbringer | Brian Moriarty | 1985 | 5 |

| 49 | 1893: A World’s Fair Mystery | Peter Nepstad | 2002 | 4 |

| = | And Then You Come to a House Not Unlike the Previous One | B. J. Best | 2021 | 4 |

| = | A Rope of Chalk | Ryan Veeder | 2020 | 4 |

| = | Babel | Ian Finley | 1997 | 4 |

| = | Bee | Emily Short | 2012 | 4 |

| = | Enchanter | Marc Blank & Dave Lebling | 1983 | 4 |

| = | Even Some More Tales from Castle Balderstone | Ryan Veeder | 2021 | 4 |

| = | Fallen London | Failbetter Games | 2009 | 4 |

| = | Galatea | Emily Short | 2000 | 4 |

| = | Inside the Facility | Arthur DiBianca | 2016 | 4 |

| = | Kerkerkruip | Victor Gijsbers et al | 2011 | 4 |

| = | Lime Ergot | Caleb Wilson | 2014 | 4 |

| = | Overboard! | inkle | 2021 | 4 |

| = | Plasmorphosis | Agnieszka Trzaska | 2022 | 4 |

| = | Queers in Love at the End of the World | Anna Anthropy | 2013 | 4 |

| = | Repeat the Ending | Drew Cook | 2023 | 4 |

| = | Ryan Veeder’s Authentic Fly Fishing | Ryan Veeder | 2019 | 4 |

| = | Slouching Towards Bedlam | Star Foster & Daniel Ravipinto | 2003 | 4 |

| = | Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom | S. John Ross | 2007 | 4 |

| = | Turandot | Victor Gijsbers | 2019 | 4 |

| = | Vespers | Jason Devlin | 2005 | 4 |

| = | With Those We Love Alive | Porpentine & Brenda Neotenomie | 2014 | 4 |

A sheet with all the games (including those that received 1, 2 or 3 votes) and their vote totals can be found here. Results of earlier years can be found here: 2011, 2015, 2019. Also of interest might be the forum topic in which the call for votes was made. The opening post contains links to discussions of earlier editions, and many of the other posts contain voters’ explanations of their votes.

Discussion

It is perhaps not too interesting to tease out little factoids such as which game lost most places, which authors had most games voted for, and so on, though anyone who wants can use the publicly available data to do so. The primary thing we would like to comment on is the apparent dominance of parser games in the Top 50.

The distinction between a parser game and a choice game is not always a useful or easy one to make. Not only does the ‘choice’ category group together many different types of interface; but the rise of ‘limited parser games,’ in which the supposed natural language parser only recognises an extremely small number of pre-given commands, as well as the existence of parser-like choice games, has made the distinction seem far from clear-cut. For purposes of this discussion, we have somewhat arbitrarily grouped all games in which you type in commands as ‘parser’, and all others as ‘choice’. (One game in the list, Coloratura, has been released in both parser and choice format. We’ll count it as half a parser and half a choice game.)

With this distinction in place, we see that among the top 17 games, there are 16 parser games and only 1 choice game (80 Days). Among the top 37 games, 30.5 are parser games and 6.5 are choice games. The entire top 70 contains 49.5 parser games and 20.5 choice games.

| Top … | # parser | # choice | % parser | % choice |

| 17 | 16 | 1 | 94% | 6% |

| 37 | 30.5 | 6.5 | 81% | 19% |

| 70 | 49.5 | 20.5 | 71% | 29% |

At first sight, these numbers seem to indicate that the community’s sense of the canon is quite parser-centric. Or it could just be the case that a higher percentage of parser enthusiasts participated in the poll. In fact, however, the numbers tell a very different story once we delve into them a little more. First, as can be seen from the table above, the percentage of choice games steadily rises as we move to the many games that received only a few votes each. What this seems to indicate is not so much a dominance of the parser, but a greater consensus about which parser games are the best ones. At least two, mutually compatible, hypotheses can explain this. First, when it comes to older games, we can notice that critical consensus is often only reached after a certain amount of time has gone by; and so it is perhaps not very surprising that there has crystallised a canon of ‘classic’ older games that does well in the Top 50. Older games are almost universally of the parser variety, so this explains in part why the very highest regions of the Top 50 are parser-centric. Now there are also some newer games up there; and here a second hypothesis can be launched. When it comes to new games, parser enthusiast simply have fewer games to choose from, and therefore, their votes will not be scattered across as many games. While we don’t have precise numbers for the amount of parser and choice games that are being published, we can note that the 2022 Interactive Fiction competition has approximately 1/3 of its games listed as parser, and this competition could well be more parser-heavy than the total output of interactive fiction games.

These hypotheses are speculative, but more enlightenment can be gained by looking at only recent games in the Top 50. If we look at games that were published in 2013 (the year after howling dogs drew attention to Twine) or later, we find the following. In the top 70, among the 33 games that were published in 2013 or later: 17.5 or 53% were choice games. If we add in the next category of games that received at least 3 votes, we arrive at 49 games, of which 30.5 or 62% were choice games. (We did not at this time put in the rather daunting work of sorting all 341 games that received votes on into choice and parser categories.) So when we put things in a historical perspective, the apparent dominance of parser games in the Top 50 is revealed as based in the fact that the parser has a longer history, not as a reflection of current interests or a selection effect among participants.

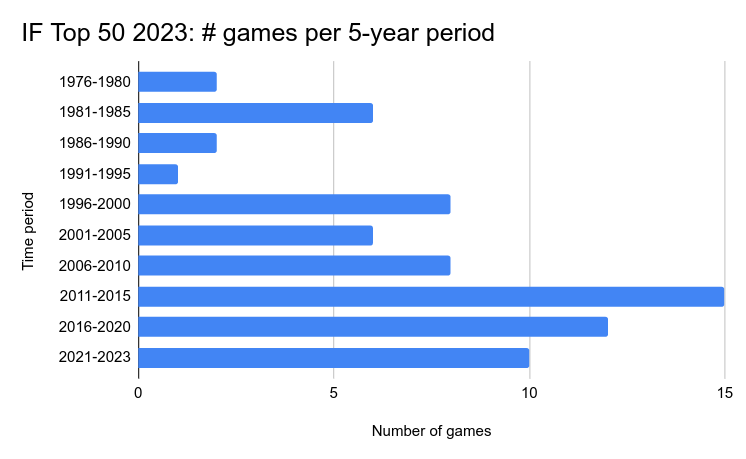

The historical distribution of games is of some independent interest, so here is a table indicating how many games in the full (70 game) Top 50 came from which 5-year period:

There’s a clear dip in the period from the late 80s to around 1995 when commercial IF was disappearing and the hobbyist age had not yet begun. It is also obvious that more recent games are very well represented (one should note that the lowest bar represents only half of 5-year time period, so there is a sense in which it contains most games per year). Possibly there’s a recency effect here, where currently active players are more likely to have played and to remember more recent games. Or perhaps the golden age of interactive fiction is now… or yet to come!

More news four years from now.