Chandler Groover discusses the design of gameplay meant to evoke the frustration of menial labor without being frustrating.

Setting the Scene

In the late 19th century, Queen Victoria struck a bargain with supernatural powers and sold the City of London. The entire metropolis—buildings, streets, and even the Thames—was subsequently engulfed by bats, plucked from England, and transported into a massive underground cavern. All the people were transported too. Now the city sits next to Hell. Lovecraftian beasts mingle with aristocrats. Dreamers can physically enter their dreams, and nightmares leak into reality.

This is the setting for Fallen London. Developed by Failbetter Games, Fallen London was first launched in 2009 and has been running continuously ever since. It’s a browser-based text game with single-player and multi-player elements. Players create characters, navigate the city’s Gothic horrors, develop skills like Glasswork (the ability to pass through mirrors) and Kataleptic Toxicology (the mastery of fantastical poisons), while striving to avoid penalties like Suspicion and Scandal.

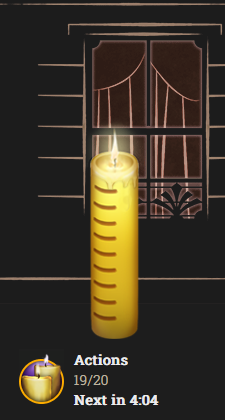

The game employs turn-based timers called Candles. By performing actions, you gradually burn down your Candle; to keep playing, you have to wait for the Candle’s flame to recharge. This means that it takes real time to complete stories in the setting, and the setting contains hundreds, each with their own plots, characters, and mechanics.

Most of Fallen London is free to play, but players can purchase premium Exceptional Stories. These stories function like DLC and plug into the base game. Because they’re self-contained, Failbetter can experiment with different narrative designs for each one. Their publication model also allows the studio to showcase work from different authors. Since April 2015, they’ve published a new story every month, and I was commissioned to write their 100th Exceptional Story: “The Bloody Wallpaper.”1

To commemorate the milestone, “The Bloody Wallpaper” is a special Exceptional Story. For one thing, it’s much longer than almost any other story in Fallen London’s catalogue. It’s also more idiosyncratic. I’d like to discuss its design, but in order to do that, it’s important to explain how it fits into the game’s overarching narrative—and how class informs that narrative.

Climbing the Social Ladder

Players can roleplay as a variety of characters in Fallen London: monster-hunters, arcane scholars, priests, bohemians, spies, and assassins (just to name a few options). No matter what roleplaying choices you make, however, everyone begins the game the same way: by breaking out of prison.

As an escaped convict, you start your journey penniless, unhoused, without friends or acquaintances. But you quickly work your way up the social ladder—by ingratiating yourself with influential figures, increasing your skills, and performing notable feats. More than anything else, you accumulate wealth—not just money, but also abstract currencies like Blackmail Material and Favours in High Places.

In the world of Fallen London, economic power has occult resonance. This underpins the game’s horror. The forces of capitalism are “cosmic principles” embedded in the universe. Social hierarchies are supernaturally mandated, and the authorities who rule London—known as the Masters of the Bazaar—have monopolized everything from iron to wine to dreams. Love itself is taxed.

A great deal of Fallen London is concerned with deconstructing the city’s economic and social systems. Entire factions, such as the Revolutionaries, are concerned with deconstructing these systems literally. Nevertheless, to advance through the game, one must climb the social ladder. After climbing high enough, the player can become a “Person of Some Importance”—with “importance” linked directly to economic influence within London’s capitalist dystopia.

In other words, if you aren’t rich, then your life isn’t important.

Of course, this is an oversimplification, especially when you consider how many stories Fallen London contains, how they each explore the setting differently, and how roleplaying can shape the game uniquely for everyone. But the core gameplay progression entrenches London’s class system, and even the most revolutionary players will ascend into royal orbits by amassing capital.

One way the text represents the player’s upper-class lifestyle is by not representing the lower-class servants who populate London—and who staff the player’s own lodgings. This narrative technique—communicating a presence via an absence—subversively echoes 19th-century British fiction, where servants are commonly taken for granted and therefore not described.2

For the game’s 100th Exceptional Story, I wanted to invert the default focus and give service work the spotlight. “The Bloody Wallpaper” strips the player’s advantages—financial, social, political—and its mechanics are designed to simulate menial labor. In this Exceptional Story, the player is conscripted to work in a luxury hotel for a single evening. But menial labor isn’t famous for being fun, and “The Bloody Wallpaper” is premium DLC for an online game: it needs to be fun, doesn’t it?

Are You Not Entertained?

The question of whether “fun” should be the primary objective of games as a medium will never have a universal answer. Players will always have personal tastes and, perhaps more importantly, individual tolerance levels for difficulty. But certain studios have built entire brands around the grueling reputation of their games. FromSoftware’s Dark Souls is marketed with the now-infamous tagline: “Prepare To Die.” Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy advertises itself as a game “made for a certain kind of person. To hurt them.” And the “bullet hell” genre has “hell” right in the name.

Then again, even these games might be said to entertain people with frustration. A dash of masochism may be necessary for players to enjoy them, but players do enjoy them. The greater the challenge, the more satisfying it is to overcome—if you’re up for a little struggle.

Fallen London itself employs grueling mechanics in the optional questline “Seeking Mr Eaten’s Name,” which repeatedly warns the player not to play it. “Seeking” is a small piece of the game, unnecessary for anyone to complete, but its warnings to “stay away” are precisely what encourage players to attempt it, frequently spurred by a sense of contrarian defiance. Nor is “Seeking” alone. Another optional questline that I wrote for Fallen London, known as “Discordant Studies,” features similar mechanics to challenge late-game players who have already leveled up most of their skills.

“Seeking” and “Discordant Studies,” however, are not only optional but also free to play. If people find them too challenging, they can simply play other questlines in Fallen London instead, and they won’t feel as though they’ve misspent their money. Games like Dark Souls and Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy come with a price-tag, but players purchase these titles because they’re difficult.

“The Bloody Wallpaper” exists at a different intersection of in-game difficulty and real-world capitalism. All of the Exceptional Stories in Fallen London’s catalogue are designed to have enjoyable mechanics, and “The Bloody Wallpaper,” by simulating the frustration of menial labor, is not just atypical for an Exceptional Story but goes against the grain of Fallen London as a whole. Prior to its publication, ninety-nine other Exceptional Stories established a consistent challenge level, setting expectations for the audience about what they were purchasing when they bought DLC for the game.

Beyond breaking away from Fallen London’s standard gameplay, “The Bloody Wallpaper” also breaks from the traditional idea in the games industry of “challenge as something to overcome.” Difficult mechanics in this Exceptional Story aren’t implemented as puzzles that will be satisfying to solve, but to evoke frustration as an emotion—and yet “The Bloody Wallpaper” can’t be too frustrating to play! It can’t really break away from Fallen London’s standard gameplay either, because it still has to function as the 100th Exceptional Story, faithfully celebrating the anniversary.

This is a tricky tightrope to walk. While appearing to challenge the player, the story needs to quietly smooth over obstacles and make everything easy to figure out. The player should enjoy the story and want to keep playing—and simultaneously dislike the labor and want to stop working! Ultimately, the tension of these contradictions should enrich the experience.

I don’t want to spend too much time discussing the plot of “The Bloody Wallpaper.” Rather, this article will explore the nuts and bolts of the story’s mechanical implementation: how the gameplay is designed to evoke frustration without being frustrating.

The Grind

Almost everyone who plays online games—and almost everyone who has held a job—will know about “the grind.” In order to get ahead, tasks must be repeated to make progress.

Fallen London is no exception. If players are roleplaying as poets, they have to grind “Inspiration” to write a sufficiently creative verse; if they’re embroiled in courtly romance, they have to grind their “Fascinating” attribute to attract a lover’s attention; and the grind for more money is never-ending. But these grinds are rarely center stage. Structurally, they’re connective tissue between larger plot points. Moreover, these grinds are dispersed throughout the city: if players need money, they can hunt giant rats for bounties, conduct heists, or dabble in espionage—and that barely scratches the surface.

“The Bloody Wallpaper” is different. In this Exceptional Story, the grind isn’t connective tissue. Instead, it’s the main feature. Not only that, but “The Bloody Wallpaper” traps the player in “a state of binding servitude” at the Royal Bethlehem Hotel until the grind is complete. Normally in Fallen London, players can move freely between areas, dropping one narrative thread to pick up another, but “The Bloody Wallpaper” restricts the player’s physical and social mobility.

I’ve already mentioned Suspicion and Scandal, which are penalties the player can acquire by failing challenges. Too much Suspicion, and you’re temporarily imprisoned. Too much Scandal, and you’re temporarily exiled. If you have too many Nightmares, that’s another penalty: after reaching a certain limit, you’re sent to the Royal Bethlehem to “relax” until your Nightmares have subsided.

In the real world, the Royal Bethlehem is a mental hospital in London. During the Victorian era, it did not have a pleasant reputation.3 But in Fallen London’s alternate history, the Royal Bethlehem is a luxury hotel. Suites are in high demand. If a player successfully reserves the penthouse, this is one of the game’s biggest achievements. Whether you have a reservation or not, however, you’re still sent to the Beth if you suffer from excessive Nightmares, and you can’t leave until you’ve reduced them.

“The Bloody Wallpaper” employs the same narrative-mechanical logic: until players reduce their Nightmares, they can’t leave the hotel. But during this Exceptional Story, rather than staying as a guest, the player is compelled by the hotel’s Manager to work as a servant. Whereas guests have many avenues to reduce their Nightmares, servants do not; their Nightmares perpetually increase, trapping them at the bottom of the social hierarchy. The grind is their only option.

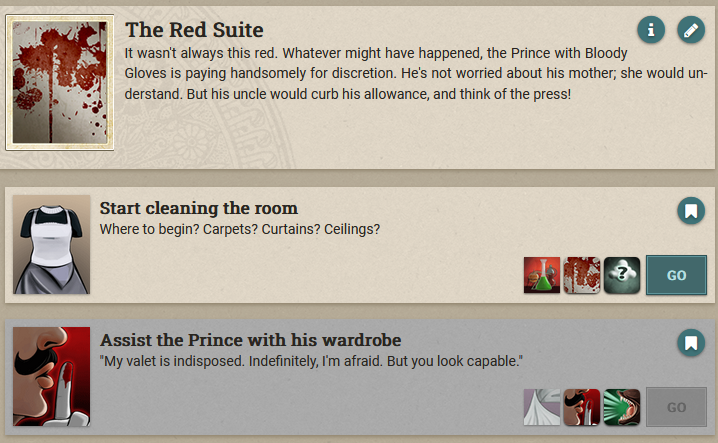

The grind, in this case, involves collecting laundry, delivering room service, and performing general housekeeping tasks. In terms of gameplay, these actions are accomplished easily—merely by clicking a button to “start cleaning the room,” for instance.

It’s simple to click a button, but every time the player does, their Candle burns down a little more, depleting their pool of available actions. What this means is that “The Bloody Wallpaper” traps the player inside the hotel in real time as a servant.

Fallen London has many currencies, but time is the game’s most valuable asset. Time is also the game’s only universally valuable asset. Certain players may have vast stores of disposable in-game wealth, but time is precious for everybody. It is only by consuming a player’s Candle, therefore, that the game can apply meaningful pressure and express hardship.

But a grind that exists purely to consume time is unlikely to be very fun… which is why “The Bloody Wallpaper” doesn’t actually feature grinding!

Elsewhere in Fallen London, if a player clicks the same button multiple times, the game will usually print the same text. Some results have procedurally generated variations, but many do not. The base game, therefore, trains the player to expect this behavior from the mechanics. Whenever new text is displayed, on the other hand, that indicates progress. At a fundamental level, players are playing the game for new text, which is the most significant reward a text-based game can deliver.

“The Bloody Wallpaper” exploits these preconceptions about the mechanics. You may have to click the same “clean the room” button multiple times, but you’ll never reread the same result. Every action in this Exceptional Story rewards the player with new text—and what this means is that the grind inside the hotel is an illusion. The player may feel like they’re running in place, stuck in a sort of narrative hamster-wheel, but the hamster-wheel is rolling forward. The story is always advancing, and each fine-grained interaction is a fresh plot point.

Working for Tips

In addition to the grind’s illusory nature, the entire purpose of grinding is also inverted. Players earn in-game monetary rewards from Fallen London’s traditional grinds, and Exceptional Stories always deliver a valuable prize at the end. “The Bloody Wallpaper” concludes with a similar payout, but that payout isn’t the story’s largest financial reward. Instead, smaller payments are sprinkled throughout the story after the player completes various tasks. Cumulatively, these add up to a sizeable amount of in-game currency—more than Exceptional Stories usually reward.

This payment scheme guarantees that everyone will receive compensation by spending their Candle’s actions inside the hotel. Due to the drip-feed nature of these smaller payments, however, players won’t get the conventional dopamine hit that they’ve come to expect from “climactic” payouts at the end of a grind. This allows the story to deliver the sensation of “underpaid labor” without underpaying the player.

Since the hotel’s guests provide some of these smaller payments in the form of tips, the payments also have thematic weight. Most tips are individually unremarkable, which makes it noteworthy when the player receives a bigger tip. This communicates narrative information about how servants might extract additional income from the hotel—and what they might have to endure.4

Whether your service is “good” or “bad,” on the other hand, isn’t a metric that “The Bloody Wallpaper” measures. Although it would be possible to program “customer satisfaction” mechanics for each NPC, the complexity of implementing such a system would expand beyond the scope of a single Exceptional Story—especially one like “The Bloody Wallpaper,” which already pushes the scope to its limit.

Instead, the system is binary: tasks are either complete or incomplete. The service that you provide, therefore, has a universal baseline, and the baseline is excellent. Your impeccable etiquette, due to its mandatory nature, feeds into the story’s nightmarish scenario, with even the smallest rebellion—such as offering lackluster service—rendered impossible.5 You may receive “good” or “bad” tips, but this depends entirely on the character of the guests, and not on your own character at all.

Upstairs and Downstairs

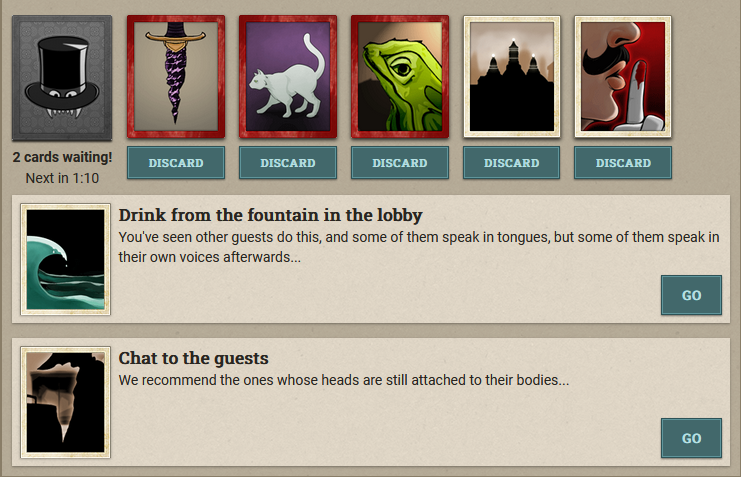

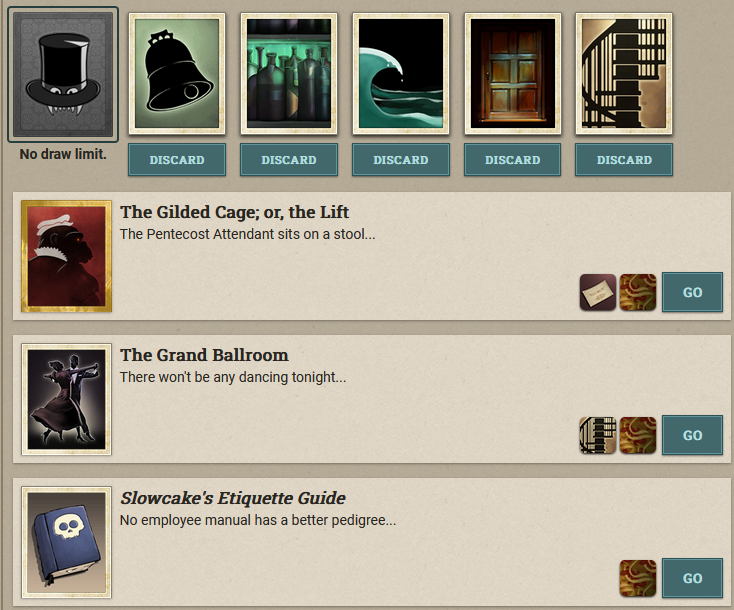

In normal gameplay, the Royal Bethlehem Hotel is a “menace zone.” These zones always feature a few permanently available “storylets” at the bottom of the screen. Storylets in Fallen London represent narrative events: each storylet has “root text,” which explains the event, followed by “branches,” which provide the player with options for how to react. Inside a menace zone, the storylets offer methods to reduce the zone’s associated penalty—Nightmares, in the Royal Beth’s case.

Each zone also features an Opportunity Deck. After clicking the deck, the player receives Opportunity Cards, which are dealt like playing cards at the top of the screen. These cards are structured similarly to the permanent storylets, but since they’re randomly dealt, players won’t always have access to the same options. Opportunity Cards in the hotel can reduce a player’s Nightmares by a greater degree than the permanent storylets—if the player is lucky enough to draw the right cards.

In the screenshot above, you can see Royal Bethlehem’s normal layout. The Opportunity Deck is in the top left corner. Five cards have already been dealt and are displayed in a line to the right of the deck. The text boxes on the bottom—“Drink from the fountain in the lobby” and “Chat to the guests”—are permanent storylets in the menace zone.

The setting of “The Bloody Wallpaper” is built to mirror this design. Just like the menace zone, it features storylets at the bottom of the screen and an Opportunity Deck at the top. Even though it’s coded as a completely separate area, the hotel inside this Exceptional Story will feel like the same hotel the player is accustomed to visiting.

Now that you’re working as a servant, though, the space inside the hotel is more expansive: you have access to areas that would be off-limits to guests. One of the permanent storylets represents a lift, which the player can take upstairs and downstairs to different floors. On every floor, the Opportunity Deck contains unique cards. Each time the player travels between floors, the Opportunity Deck resets, and the player has to click the deck again to deal more cards.

This screenshot displays the hotel’s lobby as it appears in “The Bloody Wallpaper.” The fountain is now an Opportunity Card in the player’s hand at the top of the screen. The Opportunity Deck has “No draw limit,” allowing the player to draw endless cards.

On the hotel’s upper floors, each card in the Opportunity Deck represents a guest’s room. On the lower floors, each card represents a service area, such as the kitchen or laundry. Gameplay involves taking requests from upstairs, traveling downstairs to perform the necessary labor, and then traveling upstairs again to deliver the result to the appropriate guest. For example, if the player receives a Bundle of Dirty Laundry, it must be carried downstairs for washing—whereupon the Bundle will be transformed into an Impeccably Ironed Assortment of Spotless Laundry, which must be carried back upstairs.

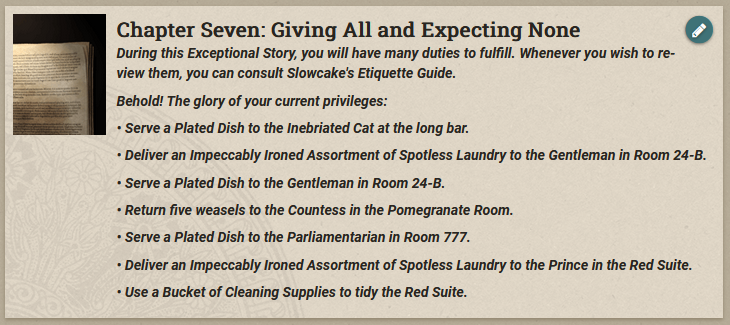

Because accomplishing these tasks is as simple as clicking a button, the “challenge” comes from navigating the hotel to click the correct buttons in the correct places. As the player makes progress through the story, guests will continuously request more services, creating an ever-growing list of demands.

With this evolving variety of errands, the player must constantly move between floors. Each time they arrive at a new floor, they’ll have to click their Opportunity Deck again, and the game will deal another hand of cards.

Fallen London almost never requires this much movement. It also never requires the Opportunity Deck to be reshuffled so persistently. The hotel’s chaos isn’t confined to the narrative; the user-interface itself embodies the pandemonium of service work, with more cards routinely spilling across the screen.

The back-and-forth grind can get overwhelming—which is the point! But this sense of being overwhelmed is an illusion too. The player might feel like they’re struggling to coordinate their duties, but one of the permanent storylets in the hotel—Slowcake’s Etiquette Guide—contains an updating task list. It tells you exactly what you have to do at any given moment.

There’s a bit of time-sensitive stress involved, too, since the story begins by instructing the player that they have “until midnight” to finish their tasks. But it’s another illusion: midnight is programmed to arrive only after you’ve completed everything.

Mini Menaces

“The Bloody Wallpaper” is nonlinear. Players can visit the hotel’s floors in any order, and they can fulfill requests from the guests in any order too. But this freedom of movement comes with a potential drawback. If the player can go anywhere, then the player can also stay in one place, monotonously performing tasks on a single floor. You might think, well, that’s grinding, isn’t it? And this Exceptional Story encourages grinding, so what’s the issue?

The issue is that the grinding in “The Bloody Wallpaper” should always remain an illusion. If the player becomes stuck doing the same repetitive action, then the story threatens to impose a real grind, which is the last thing we want. To prevent this, the story must force the player to move around the hotel, which is where two new penalties enter the picture: The Vapours and The Urge.

The Vapours6 and The Urge7 are “mini menaces” exclusive to this Exceptional Story. You start to get The Vapours whenever you use cleaning supplies, and you start to get The Urge whenever you interact with the guests. After you’ve accumulated too many points of either penalty, you won’t be able to use more cleaning supplies or serve more guests without reducing The Vapours and The Urge back to zero. In order to reduce them, you must visit the hotel’s lower floors to seek treatment.

You won’t actually suffer negative consequences if The Vapours or The Urge rise too high. Their primary purpose is to put a limit on how many actions the player can perform upstairs before being required to switch gears and travel downstairs. The Urge has a maximum level of 7, which the player must hit before treatment becomes available. But the maximum level for The Vapours is 3. The player will hit this faster. You can reduce The Vapours anytime, however, without waiting to hit the maximum level.

These different thresholds add variety to the player’s range of “compulsory” movement. If the player is already downstairs, they might choose to click the button that reduces The Vapours, even if they only have 1 or 2 points of The Vapours. Or they might choose to ignore that button and wait until The Vapours reaches the maximum level of 3 before seeking treatment.

Because you must hit the maximum level of 7 with The Urge before reducing it, this mini menace has a secondary purpose: it serves as a linear spine for the nonlinear story. Although no two players will finish their errands in the same order, every player will hit level 7 of The Urge consistently. When players go downstairs to reduce The Urge, the text can deliver important plot points at predetermined intervals.

Threading plot points through a nonlinear story by attaching them to a linear spine isn’t an uncommon technique, but like many components of “The Bloody Wallpaper,” this spine has a certain illusory property. The spine isn’t presented as a spine. It’s off to the side of the story—something that you encounter “incidentally.” The plot points should initially seem like pieces of trivia, but they lay important groundwork for the climax.

Narrative Integration

Exceptional Stories occupy a unique space in the overall narrative of Fallen London. Although they’re standalone stories, they still depend on the surrounding game to provide context. In this respect, they can’t stand alone. If someone tried to play an Exceptional Story without having played Fallen London, most stories would make little sense.

At the same time, once an Exceptional Story is finished, it’s finished. Completing a story might reward the player with a small perk like an inventory item, but Exceptional Stories can’t impact the setting too significantly. There are simply too many stories! If each one added something new to the base game, the complexity of the implementation would grow exponentially.

This poses a challenge when writing Exceptional Stories: how do you make the story matter if the narrative consequences will rarely extend beyond the story itself?

Some stories lean away from connections to the base game. If their plots are self-contained and they feature new NPCs, it’s easier for Exceptional Stories to incorporate moments of heightened drama. For example, you could write a story in which an NPC’s life is at stake. If the NPC only appears during one Exceptional Story, they might really die, since they won’t need to reappear elsewhere.

But there’s a trade-off: if you only encounter an NPC in one story, you might feel like they’re not “truly” living in London. Even if the stakes are higher within the story, the stakes might feel lower within the setting at large.

To counteract this, “The Bloody Wallpaper” leans into connections to the base game by incorporating pre-existing NPCs. Nothing too extreme can happen to them, of course, since they already have roles in Fallen London, and their roles must remain intact. But what Exceptional Stories can do is give players another lens through which to view these characters—and such lenses, which exist within the player’s mind and don’t require mechanical implementation, can have large impacts.

As the 100th Exceptional Story, “The Bloody Wallpaper” needed to leave a bigger impact than normal. I wanted to weave multiple characters from the base game into the plot, and a hotel is the perfect place to encounter NPCs from all walks of life.8

During your shift at the hotel, you interact with prominent guests: aristocrats, kings, ambassadors, politicians. If an average Londoner tried to meet them, these NPCs would be inaccessible, but for the length of this Exceptional Story, you’re one of the city’s “invisible” laborers—exactly the sort of person whose existence your own character usually takes for granted. With the hierarchy inverted, now the upper-class NPCs take you for granted.

Your “invisibility” has mechanical repercussions. If your character has met these NPCs before, and if the game has given you items or attributes to track the status of your acquaintance with them, those items and attributes now cease to matter. Because you’re a servant, the NPCs don’t perceive you as a person and don’t recognize you. Your social connections are irrelevant. In other words, your “invisibility” has invisible repercussions on the mechanics, with this Exceptional Story refusing to acknowledge your character’s past accomplishments.

But there’s an upside to being invisible: the hotel’s guests have loose lips around servants, since servants are not “Persons of Some Importance” and therefore don’t matter. As a consequence, this Exceptional Story offers backstage glimpses into some of the setting’s most esoteric lore, such as the political intrigues of various dream-dwelling NPCs. Secrets percolate everywhere in the hotel.

Apart from in-game monetary rewards, knowledge itself is a prize in Fallen London. Piecing together the lore is a major element of the game’s appeal, and “The Bloody Wallpaper” is filled with revelations about the guests. But in a story about service work, I didn’t want the upper-class NPCs to get all the attention. Most of the text is devoted to the experience of the lower-class employees, and the story’s greatest revelations are centered around the hotel and how it operates.

Even if you’re already familiar with the Royal Bethlehem, the base game only showcases its public-facing areas. “The Bloody Wallpaper” exposes the Beth’s internal bureaucracy, revealing details about the Manager… and the Assistant Manager, the Regional Manager, the Owners, the Accountants, and a wide variety of Staff Members9—plus the landlords and tax-collectors. If you were only staying as a guest, you would never learn about these characters. Indeed, the hotel would suppress knowledge of their existence, papering over the unglamorous realities of the business to promote an illusion of effortless luxury. Working behind the scenes, however, you see how the sausage gets made.

Dreams and Nightmares

The Urge provides a linear spine that extends through the story, but it’s not a spine that the player can easily see. Since progression is so fragmented, however, and since the story is so long, the player needs some method to estimate their time spent and time remaining. For that purpose, “The Bloody Wallpaper” features a progress bar in the form of a “dream” called Nothing Gold Can Stay.

There are many dreams in Fallen London.10 Most are coded as “pyramidal qualities,” which means that the player needs one point to unlock the first level of the dream, two points to unlock the second, three for the third, etc. As more levels are unlocked, the dreams add new Opportunity Cards to the base game. These cards tell dream-related stories.

Nothing Gold Can Stay doesn’t work like the other dreams in Fallen London. It’s not pyramidal. It doesn’t have different levels to unlock. Instead, it has a progress bar with a maximum level: 77.11 Each time the player completes a task, they earn another point, and the progress bar increases.

Mechanically, the progress bar provides a concrete goal for the player. Even though there are many different errands to run, they all contribute points to the same dream. By looking at the progress bar, the player knows what percentage of the Exceptional Story they’ve already completed.

Narratively, the progress bar is significant because it breaks the pattern for how dreams are coded. Something is unusual about this one. Eventually, the player will realize that it doesn’t behave like the others because the Manager of the Royal Bethlehem is controlling it. The entire Exceptional Story takes place within the dream. When your shift is over, the Manager harvests the dream from your mind. Then you can finally leave the hotel—just like you can normally leave the Royal Beth’s menace zone after your Nightmares have been reduced.

Peeling the Wallpaper

After finishing your assignments, the Manager gives you one final task: he asks you to strip the titular wallpaper from every room in the hotel. This wallpaper-peeling sequence is the story’s climax. Although it constitutes a sizeable chunk of the narrative, players will not deplete their Candles by performing this specific task. Instead, each button has a 0-action cost during the climax.

This brings me back to the role of time in “The Bloody Wallpaper,” and to the value of time as a currency in Fallen London. By requiring the player to perform so many menial duties, “The Bloody Wallpaper” depletes your Candle, trapping you in the hotel. Every player will reach a point during the story where, having burnt their Candles to stumps, they will have to wait for the flames to recharge.

Usually when this happens in Fallen London, the player won’t have anything else to do. Most buttons in the game have a 1-action cost. If you can’t click any buttons because your Candle has melted away, then you won’t be able to read most branches in the game—unless they cost 0 actions.

“The Bloody Wallpaper” has quite a few 0-action branches. Whenever you travel between floors, movement costs 0 actions. Whenever you speak to the Manager, conversation costs 0 actions. Once you’ve finished serving a guest, you’ll be able to check on the guest again—at a cost of 0 actions—and the guest will often share important information.

With so many 0-action branches, players can still explore the hotel and experience little nuggets of interaction even when their Candles are exhausted. These nuggets won’t completely occupy them while they’re waiting for their Candles to recharge, but the branches provide more “free” text than usual.

During the climax, when every option is a 0-action branch, this is much more free text than usual. By decoupling plot progression from the Candle’s action limit, “The Bloody Wallpaper” allows the player to barrel towards the end of the story. Rather than trapping the player, the mechanics now propel the player, releasing all the narrative pressure which the grind has been building since the start.

At this point in the story, it’s midnight. The player’s shift at the hotel should be over, but the Manager ekes a few more actions out of you. When he makes his final demand, requiring you to strip the wallpaper, he’s technically asking you to work overtime—which is one reason the task doesn’t technically cost any actions. You’re working, but you’re “off the clock.” You may be expending effort, but you’re not expending time. Your Candle doesn’t burn down (very much).

Each room in the hotel has wallpaper, and each room is represented by an Opportunity Card. When you strip the wallpaper from a room, you can’t draw that room’s card anymore. As you remove the wallpaper, therefore, you’re also removing cards from your Opportunity Deck.

Eventually, when you click on the deck to draw more cards, there won’t be enough left to completely fill your hand; spots on the screen will remain blank. But you’ll have to keep stripping the wallpaper. The story will present you with no other options. Room by room, and card by card, you’ll dismantle the user-interface. Working behind the scenes as a servant, you’re working inside the hotel’s mechanics. By stripping features from the hotel, you’re also stripping features from the game.

Clocking Out

“The Bloody Wallpaper” is designed to evoke feelings of disorientation, exasperation, and powerlessness. It’s also designed to be entertaining, with engaging gameplay, clear mechanics, and—perhaps most importantly—comedy. Humor is a vital ingredient in Fallen London, and it’s especially relevant here. Without humor, the experience of working at the Royal Bethlehem would be too grueling for this format of interactive fiction. If you’re laughing, however, the labor is more bearable. If you’re learning secrets about the hotel and the guests, you’ll also have more incentive to keep playing.

But why should the player be subjected to menial labor in the first place? Whether humor lightens the mood or not, why doesn’t “The Bloody Wallpaper” simply strive to be fun without frustration?

Normally, I would leave such questions for players to consider. When authors start discussing the meaning behind what they’ve written, it can stifle the audience’s own interpretation; for that reason, there are dimensions to the plot of “The Bloody Wallpaper” that I haven’t mentioned, and that I don’t plan to mention. But this Exceptional Story sits at an odd juncture in the literal marketplace of ideas: it’s a product of labor, and it’s about labor; it’s designed to critique capitalist drudgery, but it must appeal to consumers in a capitalist system. Even this article is a cog in the system, with its discussion of implementation techniques for “player-friendly” frustration. What message is “The Bloody Wallpaper” really sending, and who is receiving it?

If someone has never worked in the service industry, then playing this Exceptional Story, of course, might provide a basic level of insight. Being able to feel the grind through the gameplay is radically different than just being told about it. Or perhaps someone has service-industry experience, but not hospitality experience; perhaps they have hospitality experience, but not luxury hospitality experience—in which case, “The Bloody Wallpaper” might still offer new perspectives while providing entertainment.

The vast majority of the game’s audience, however, does not belong to the elite social class whose members conscript you into servitude in this story. It’s common for people to play Fallen London as an escape from the harsh reality of our own capitalist society—even if the dystopian hellscape of an alternate-history Victorian era might not seem the likeliest escape. For those players, the game offers a little breathing room while also reflecting contemporary problems. Like holding a carnival mirror up to modern life, Fallen London twists the world into bizarre shapes, revealing new angles from which to view difficult issues—and making people laugh at the same time.

2023 was a challenging year for me personally, and I wrote “The Bloody Wallpaper” at a low point. Despite my own life’s stressful circumstances—and also because of them—I wanted to design an Exceptional Story that would brighten the player’s day. “The Bloody Wallpaper” is meant to evoke frustration, but also to evoke a sense of understanding. If the narrative works as intended, then the player character might struggle through their shift at the hotel, but the player should feel that the text is sympathetic, and the overall experience should hopefully be uplifting.

At the same time, I didn’t want players to come away with the impression that their job at the Royal Beth wastheworstLondon has to offer. If this Exceptional Story is funny, narratively and financially rewarding, and mechanically easy to play, then it can’t be anywhere close to the worst! This is why, when you clock out and leave the hotel, the text explicitly establishes that you were working during a slow night. All of the troubles that your character experienced are trivial to the lower-class servants.

This division between the player and the player character is always relevant, and it’s central in “The Bloody Wallpaper.” After the story, you’ll plunge right back into Fallen London’s base game and continue to climb the social ladder. Since literal divinities are sitting at the top, even the wealthiest characters will still have a long ascent ahead of them. But just as “The Bloody Wallpaper” provides you with new lenses to view certain NPCs, it also provides you with new lenses to view the entire system—and your character’s position within that system—if you choose to look from a different angle.

Footnotes

You could discuss this article on the intfiction.org forums.

1 You may detect an echo between the title of this Exceptional Story and “The Yellow Wallpaper,” a classic short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman first published in 1892. You may also notice that more than the titles echo. An analysis of their thematic acoustics, however, would require its own article. But while we’re listening for echoes, here’s another: “Delightful Wallpaper,” the 2006 text adventure by Andrew Plotkin.

2 Certain stories in Fallen London bring these undescribed servants to the foreground, such as “The Frequently Deceased,” which was written by Emily Short and released in 2016.

3 The word “bedlam” is derived from the hospital’s nickname.

4 Of course, when guests don’t tip, that’s meaningful too.

5 Impossible, that is, until the end of the Exceptional Story, when you’re finally presented with a chance to release some pressure. But it’s important to remember that “The Bloody Wallpaper” doesn’t exist in a vacuum: within the context of Fallen London, rebellion is far from impossible.

6 Historically, a wide-ranging cornucopia of unrelated mental and physical ailments (some less legitimately diagnosed than others) were lumped together and attributed to “the vapours.” The Vapours in this Exceptional Story are not quite the same as the historical “malady,” but there is overlap.

7 The Urge is undefined by the narrative, but it represents a growing impulse to react “inappropriately” to any given situation. If you’ve worked in the service industry, you’ll be familiar with it.

8 Having worked at a luxury resort, this premise also allowed me to draw directly on personal experience to write the story. Considering that it’s set in a nightmare version of Victorian London, “The Bloody Wallpaper” is autobiographical to a frightening degree.

9 Among these Staff Members, immigrants and women constitute a not-insignificant percentage. However, it would take another article (if not an entire series) to even begin to explore the roles of gender, race, and nationality in the hospitality industry—in Fallen London generally, in this Exceptional Story specifically, and in the space where reality intersects with the game’s fiction.

10 Fallen London’s dreams have formulaic titles. “Having Recurring Dreams: What the Thunder Said” is one dream in the base game, and every dream features the same “Having Recurring Dreams” label. “What the Thunder Said” is a reference to “The Waste Land” by T.S. Eliot, which is referenced by many other dreams. Not every dream will reference Eliot, but every dream will reference a poem: this is the in-game formula. The dream in “The Bloody Wallpaper” is no different, but the poetic reference is slightly “off.” It’s a reference to Robert Frost, who is otherwise unlinked to Fallen London’s dream cycles. The flavor of the reference is “off” too, suggesting that the “Nothing Gold” dream is entering the player’s mind through a different route than usual.

11 Whenever the number 7 appears in Fallen London, it carries a thematic connection to the Master of Dreams, who plays a central role in the “Seeking Mr Eaten’s Name” questline. Some players might overlook the 77 on the progress bar, but for other players, this will provide an early hint that the Master’s influence is permeating the story. Even the most mechanical elements of Fallen London’sgameplay will often have narrative weight.